|

Mark Sennett

Managing Editor |

|

Kelly Rose

Editor |

| Home> | PPE | >General PPE | >Suitably dressed? |

| Home> | PPE | >Protective Clothing | >Suitably dressed? |

Suitably dressed?

24 February 2025

Martin Lill looks at how (not to) select hazmat clothing for protection against toxic chemicals and explains the common errors in the selection of chemical protective clothing.

USEFUL GUIDANCE on how to select PPE for hazardous materials is plentiful. However, it can be at least as useful to consider how not to do it, addressing common errors made.

Chemicals present a challenge different to most hazards. If a brick falls on your head, or if you are hit by the heat of an arc-flash, it is impossible to not notice.

Toxic chemicals, however, can contaminate and absorb through the skin unnoticed, resulting in devastating health effects (cancers, organ damage, developmental problems etc) months, years, even decades later. Thus, an assumption that no contamination is occurring with your current chemical suit simply because you have not had any problems is flawed. Contamination might well have occurred; the health consequences simply have not yet developed.

This insidious nature of the hazard means greater care is required in PPE selection and use. Assumptions must be avoided. And there are three dangerous assumption commonly made.

- That a coverall with hood provides full body protection

The coverall with hood is the most common style used. Certified to EN Types 3 and 4 (perhaps misleadingly, to “full body”, not “partial body”, protection). Specifiers often assume this offers full body protection.

Yet clearly it leaves the face, hands and feet exposed. Other PPE – face-mask, gloves and boots must be added. But what about joins between the different PPE? They represent gaps through which a liquid – or especially a vapourised chemical – will penetrate.

Steps can be taken to seal those joins with adhesive tape, but how effective is this? What training and quality control is in place to ensure a seal? Is on-site testing undertaken to confirm it? The answer of course, in most cases, “Unknown”, “None” and “No”. Sealing of joins in this way is more of a hope of protection than a certainty.

Certification to relevant EN standards includes a “Type Test”, measuring whole suit inward leakage with a pass or fail result. Does this ensure whole suit protection?

Unfortunately, no. For two reasons:

- PPE joins are carefully sealed, often with multiple layers of tape, and far more conscientiously than is likely to happen in the real world. Why? Because otherwise garments would fail (somewhat proving the point).

- Even with taping, a “pass” does not necessarily indicate no inward leakage because a low level of leakage is allowed.

Only a gas-tight suit gives certainty of zero leakage, and budgets normally mean this is not an option. The reality is, when wearing a coverall with hood some level of inward leakage is almost inevitable – especially with chemicals that vapourise. For highly toxic contaminants with no immediate effects, that is important to understand.

- Excessive focus on the permeation resistance test

The permeation test (EN6529) measures the resistance of fabric to permeation of specific chemicals and has become the “catch-all” indication of safety when choosing a suit. It provides a permeation “breakthrough time”, which is too often solely relied on as an indication of protection.

But it is conducted only on garment fabric, so ignores elements such as seams which may be less resistant than the fabric, the zipper, and, of course, the joins with other PPE.

Furthermore, permeation through a barrier is a molecular event dealing with very small volumes measured in micrograms. Leakage by penetration through gaps is likely to involve much larger volumes. So, an over-reliance on the permeation test risks ignoring the greater risk.

- Misunderstanding of the permeation resistance test

To compound this, the permeation test is widely misunderstood. Most users assume (not unreasonably) that “breakthrough” is when the chemical first “breaks through” the fabric, therefor proving a suit offers protection.

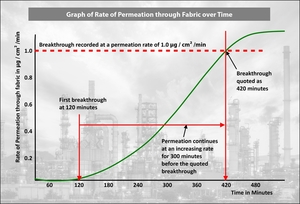

But this is a misunderstanding. “Breakthrough” (more correctly, “Normalised Breakthrough”) in this context is the time until the rate of permeation through the fabric reaches a particular speed (in the case of the EN test, usually 1.0µg/cm2/min).

The significance is that the chemical permeates through the fabric before the breakthrough time! This is explained in Figure 1, in which breakthrough time would be quoted as 420 minutes, yet first breakthrough occurs at only 120 minutes.

Fig 1: showing permeation rate over time

Making any one of these three assumptions and failing to address the implications can mean that workers are not as well protected as they should be. Low level, regular, unnoticed contamination could be a fact. If the chemical has chronic toxicity, this could have grave consequences for the workers’ future health.

What do we do about it?

There are four changes in approach to address these challenges and minimise the risk: -

- Understand the chemical and the hazard it presents

Is it dermal toxicity? What are the long-term consequences? Will it vapourise easily? Will contamination be noticed? Most importantly, how much of it is required to cause harm?

- Don’t assume a coverall with hood, certified or not, provides full body protection. Some level of inward leakage is likely, and steps should be taken to mitigate it, and to be sure the volume will not cause harm. With highly toxic, vapourising chemicals a gas-tight suit might be the only safe option.

- Permeation test breakthrough is not an indication of safety. It ignores the possibly greater hazard of whole suit leakage – and is widely misunderstood anyway!

- Think “Safe-Wear Time”. Short of wearing a gas-tight suit, some inward leakage is likely, so be sure that it remains below the level at which might cause harm. Safe-Wear Time is the maximum time a wearer should remain with potential exposure to the chemical before total leakage might be harmful.

Toxic chemicals are an insidious hazard. Contamination may not even be noticed, yet the consequences of even low level contamination could be life-changing if not life ending. Protecting workers is not just about protecting them now. Employers responsibility extends to protecting them from future effects of hazards as well as immediate, so in selecting hazmat suits and managing their use, it is important to avoid these common assumptions. Failure to do so might mean workers are not be as well protected as they should be.

Martin Lill is product marketing director at Lakeland Industries. For more information, visit www.lakeland.com

- Twelve Tips to help ensure Safety Clothing Protects as it should.

- A dangerous combination?

- Understanding EU and US PPE Standards

- Dress for success

- Hazmat suit donning and doffing

- Can you assume you are safe in a chemical suit certified for Type 3, 4, 5 or 6 protection?

- How do you solve the problem of uncomfortable chemical suits?

- Covid-19: A challenge to protective clothing manufacturers

- The way you assess how long you can use your chemical suit is changing! Find out how with Lakeland at A+A 19.

- Garment design and construction in chemical suits